Estimated read time is 4 minutes — enjoy!

Very likely, no one needs me to tell them that Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead—which I finished this week—is a great book. It did win the Pulitzer, after all. It’s been reviewed—beautifully and insightfully—by critics across the literary world. But I’ll still add my voice to the chorus: the novel is excellent. The narrator, a red-headed boy growing up in modern-day Appalachia, is one of the most engaging characters I’ve encountered in years. His blend of sarcasm, sadness, grit, and wit breathes real life into a story that’s often harrowing.

Kingsolver’s depiction of rural life is richly drawn—not just the crushing poverty or broken institutions, but also the humor, the local connections, the central role of high school football, and the small-town social structures that hold communities together. And perhaps most importantly, she paints a devastating portrait of how opioids tore through places left behind by globalization and the energy revolution. It’s the kind of sweeping, compassionate storytelling we need more of in a nation that too often forgets its rural corners exist.

But while Demon Copperhead deserves every bit of praise it’s received, I want to push back on one interpretation I’ve heard from several commentators: that it serves as a progressive counterweight to J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy. That comparison only goes so far—and politically, I think it obscures more than it reveals.

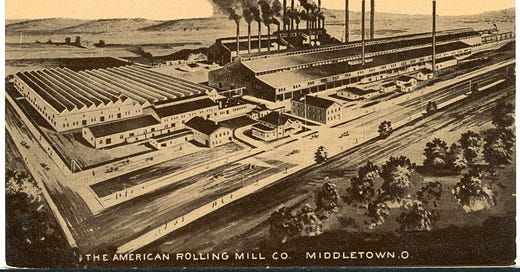

One major difference is geographic. Vance splits his memoir between Jackson, Kentucky—his family’s ancestral home in Appalachia—and Middletown, Ohio, where he grew up. While he casts Middletown as a rural town, it’s actually a sizable community. I live about 45 minutes away, and my son has played soccer games there for years in the shadow of one of the few remaining steel mills in America. Middletown isn’t a tiny town tucked into the hills; it’s a small post-industrial city. And its economic decline wasn’t driven primarily by globalization, but by automation. The plant still produces about the same amount of steel—it just does so with far fewer workers.

Situated along the I-75 corridor between Cincinnati and Dayton, Middletown is part of a broad exurban zone that links the two cities. Yes, the surrounding region includes sprawling corn and soy fields—but most residents live in one of two large, politically purple metro regions (Middletown is officially part of the Cincinnati metropolitan statistical area). By contrast, Kingsolver’s novel is rooted in truly rural geography: isolated hills, tight-knit towns, and the overlooked corners of Appalachia.

This distinction matters because our modern political divide often follows the contours of geography. Appalachia has become shorthand for “rural America,” and rural America, in turn, has become shorthand for “conservative.” Much of the conversation around these books assumes that if progressives better understood these regions—as Kingsolver helps us do—they might win them back. Maybe. But I’d argue that this approach misunderstands both the strengths and the real challenges facing the Democratic Party.

As I argue in Closing the Urban-Rural Power Divide, the most pressing political fact of our time is that over 80% of Americans now live in metropolitan regions. That doesn’t mean we should ignore rural voters—far from it. They are Americans. Many are poor. They deserve a responsive government. They also provide the food, minerals, energy, and open space that cities depend on. But trying to win back rural America by adopting its cultural values is a losing proposition. Progressives shouldn’t trade away equality, pluralism, or science for marginal gains in counties with shrinking populations.

Instead, we need a new coalitional strategy—one that continues to gain ground with urban voters and college-educated Americans, while also rebuilding bridges to the mostly urban working class. That bridge must be built on economic fairness, not cultural pandering. It must grapple with the structural imbalance of our federal system, which gives rural areas outsized power even as their populations decline.

Kingsolver’s novel helps us feel the pain of places often ignored in policy debates. That’s an immense contribution. But empathy alone won’t fix a political system that routinely elevates minority rule. To do that, we need structural change—and a strategy that puts economic justice front and center without abandoning the moral and demographic base of the progressive movement. One of the key objectives of Thor’s Forge will always be to explore how to make that strategy a reality.

COMING NEXT MONDAY: we’ll dive into America’s second political age—a long stretch of Republican dominance, during which the party repeatedly reinvented itself while Democrats struggled to stay relevant on the national stage.

Thanks for the read and the comment! I can only imagine how much the book means to someone from WV, given that I grew up as a working class kid in Alaska (about as far away from WV as can be imagined!), and the book rang true to my experience growing up in a similar time.

I enjoyed reading your take on Demon Copperhead and agree with you for the most part. My first pass though “DC” hit me emotionally - Demon and I would be very close in age if he wasn’t a fictional character. His struggles rang too true with my own experiences in southern WV.

I’ll reread DC from a more analytical place in the future but DC is written from a place that is deeply, culturally Appalachian. Hillbilly Elegy is barely skims that surface.